Colombian Exoskeletons: The Beginning of a Revolution

By: Ronny Suárez

Photos: Fotos Alberto Sierra DOI https://doi.org/10.12804/dvcn_10336.42361_num7

Science and Tech

By: Ronny Suárez

Photos: Fotos Alberto Sierra DOI https://doi.org/10.12804/dvcn_10336.42361_num7

Imagine for a second about the daily work of a coffee picker in Colombia: long and demanding days, outdoors, in the sun or rain, going back and forth through mountainous terrain in search of ripe fruits, carrying baskets or cloth bags to collect coffee beans by hand. Now think about your back, which involves a crouched posture and repeated movements for hours.

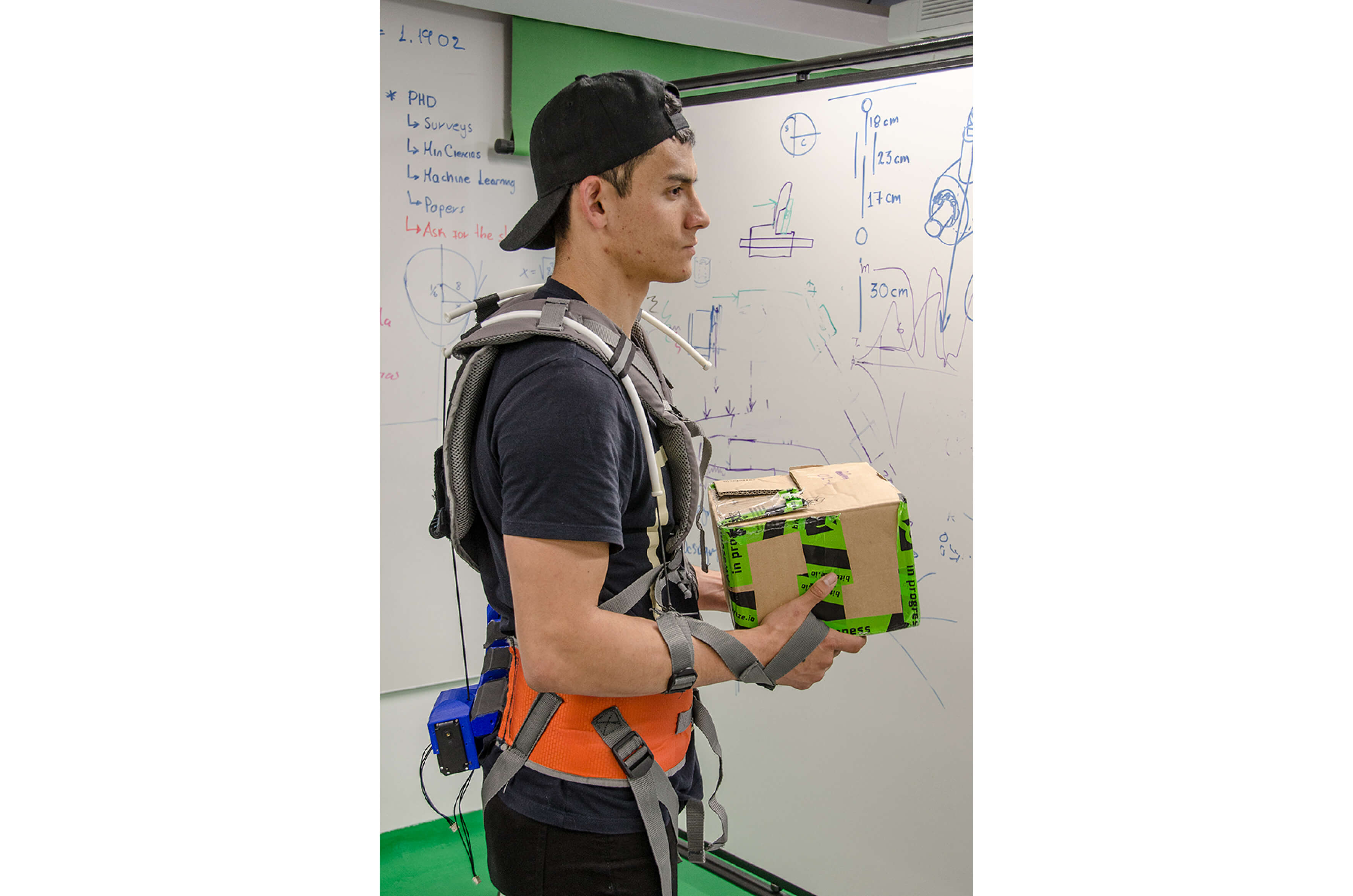

Diego Fernando Casas Bocanegra, a PhD student in Engineering, Science and Technology, is working on his project to create exoskeletons.

The thousands of workers in this important productive sector –the Coffee Information System (Sica) estimates that there are 48000 families dedicated to coffee production in the country– are exposed to an imminent risk of developing musculoskeletal disorders in the back, shoulders and wrists due to the constant physical load and the use of tools and materials that are not ergonomic to carry out their tasks.

Professor Juan Alberto Castillo Martínez, from the School of Medicine and Health Sciences (EMCS) of the Universidad del Rosario, has studied for several years how to improve the quality of life of workers like them, from the area of ergonomics and movement sciences. In fact, his first steps in the academy, when he was based in Manizales, he dedicated them to trying to provide solutions to the challenges of the process of collecting the national product par excellence, while advancing his scientific studies in the Coffee Research Center (Cenicafé) There, together with other researchers and students of the Agricultural Engineering Unit, he began to develop basic and accessible technologies to improve the harvesting process and the conditions of the collectors.

At the beginning, these were basic assistance tools, such as hand extensions to optimize the taking of the fruit, innovations without much technology yet, as Castillo himself acknowledges. However, it was the beginning of a path that could very possibly create real- life solutions for thousands of workers in different productive sectors, and even for people with mobility disorders or limitations

Those solutions materialized into wearable exoskeletons with electronic and mechanical structures that to many might look like the stuff of 1980s science fiction movies or gadgets used by modern superheroes.

Castillo, who holds a master's degree in Ergonomics and a doctorate in Cognitive Psychology, from Lumière University (Lyon, France) and postdoctoral studies in motion sciences in Italy, describes exoskeletons as wearable robotic devices that can improve productive capacity and protect people's health. In simpler words, they make it easier to do tasks and prevent future injuries.

His co-teammate during the last years has been Mario Fernando Jiménez Hernández, professor and director of Research of the School of Engineering, Science and Technology (EICT) of the Universidad del Rosario. Jiménez is a bit more pragmatic than Castillo when it comes to defining exoskeletons: “It is wearable technology that supports and assists the movement for the sake of the well-being and health of those who use it.”

From the lab to real life

The Castillo laboratory, in which Jiménez works hard, has so far developed 10 software programs and five technologies aimed at improving and protecting the health of workers. Of the latter, two are already patented and the other three are on track to be patented.

Today both projects work in parallel in order to accelerate the incorporation of exoskeletons developed in Colombia into the working lives of thousands of workers. One of them, for example, advanced in partnership with the researcherCarlos Andrés Cifuentesof the Bristol Robotics Laboratory, seeks to create an elbow exoskeleton to increase the strength in the lifting and transport of heavy objects.

This development is in the testing and configuration stage of the concept for its effective manufacture.

Musculoskeletal disorders a major burden for the country

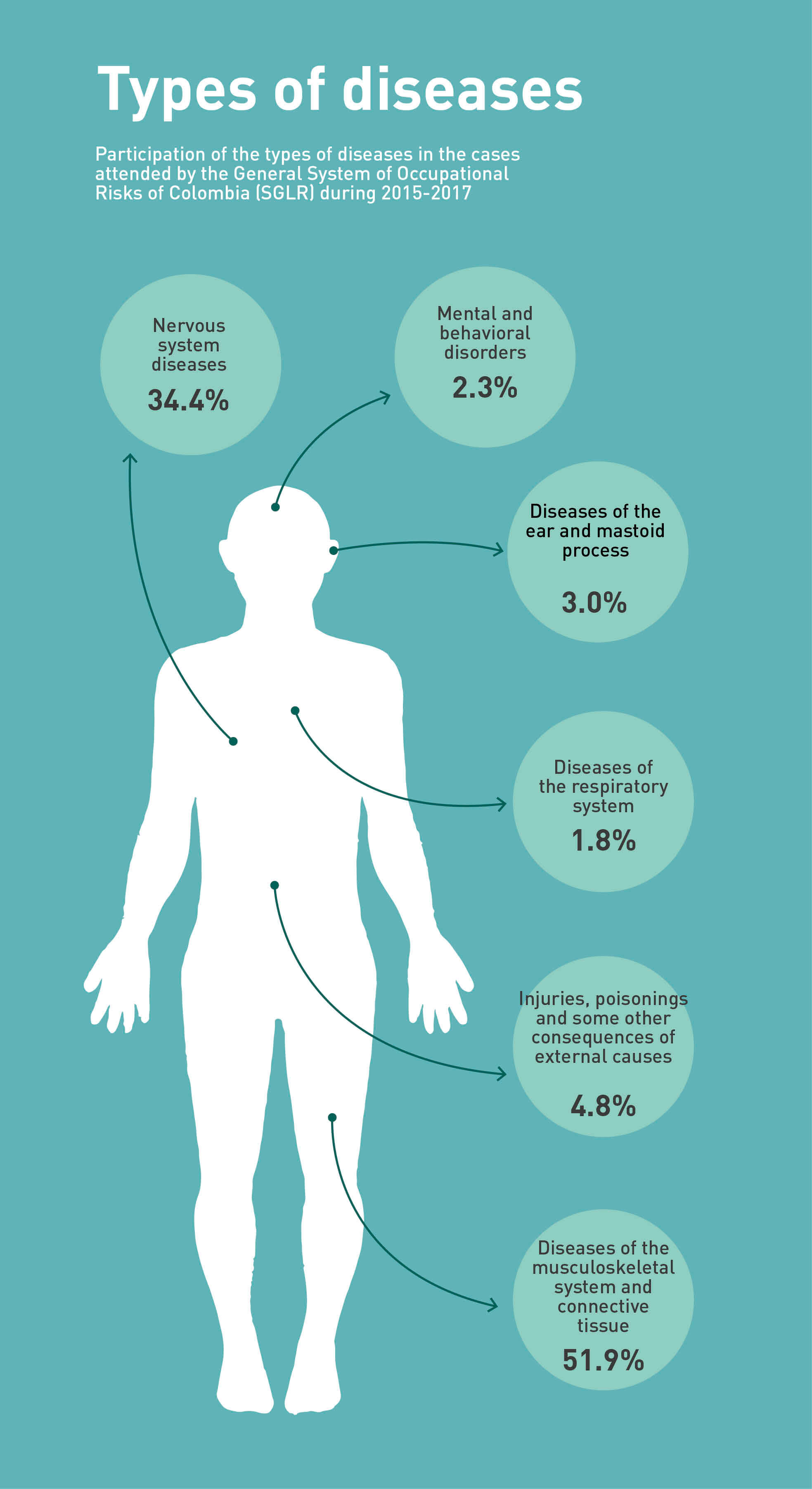

According to a report by the Federation of Colombian Insurers (Fasecolda), diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue were the most registered in the general system of occupational risks between 2015 and 2017, with 51.9 percent, well ahead of other causes such as nervous system ailments, injuries or mental disorders.

This is undoubtedly a public health problem, given that Fasecolda rated 31 562 occupational diseases in 2022. 48.7 percent of the cases were caused by forced postures and repetitive movements, according to a 2020 estimate by Martha Mendinueta Martínez, a professor at Simón Bolívar University. Most worryingly, in one in four cases, some form of permanent disability is generated.

Juan Vicente Conde Sierra, specialist in Occupational Medicine and member of the board of directors of the Colombian society of that specialty, explains that “some of these diseases are tendinitis, tenosynovitis, bursitis and carpal tunnel syndrome” and warns about the considerable underdiagnosis of these occupational diseases, which makes it difficult to recognize and treat them properly. “Many times, deaths from diseases like cancer and respiratory diseases are not related to working conditions, which leads to underreporting,” he concludes.

Conde Sierra highlights the importance of exoskeletons as a tool to prevent and treat these diseases, whether those that help to rest in a semi-seated position, those that increase the strength and resistance of the worker or motorized ones that can help people with disabilities to recover lost functions.

This development is in the testing and configuration stage of the concept for its effective manufacture.

To get to this point they carried out a study with workers of a parcel and goods transport company, whose main objective was to record the musculoskeletal problems they experienced in their daily lives, especially in their elbows and upper limbs. They used wearable devices and inertial technology (which acts by returning the force it generates to the individual) to quantitatively measure variables of movement and fatigue.

This specific exoskeleton uses non-rigid technology, which means it does not limit the degrees of freedom of human movement, as some devices already on the market do. The goal is for them to assist and not limit people's natural movements, which could delay the onset of fatigue by performing repetitive movements.

Although the project originated with an industrial focus, researchers recognize that the device has applications beyond of labor assistance.

“The first two causes of loss of life years that can be lived with a disability are related to musculoskeletal injuries. This means that it is a field where many contributions and technological solutions are required and that are accessible to help people stay functional and operational,” says Professor Castillo.

Jiménez, who initially focused on the agricultural and agro-industrial field, and after her PhD focused on robotics, assistance and rehabilitation, is clear in saying that “these devices have potential applications in everyday life and even in clinics, taking into account the enormous burden of the disease that disorders of the type mentioned above cause in Colombia and in the world (see box).”

A long way

Are we, then, far from seeing these robotic exoskeletons applied in daily life? Researchers are cautious and prefer to be optimistic in estimating the potential of these devices. In fact, they point out that there are already robust exoskeletons that can assist those in need on the march and in other activities, although, of course, not in a generalized way.

“Businesses want development ‘right now’… but we are going at a different speed academically. We have validation phases that we must comply with to ensure that the devices do fulfill their purpose,” says Professor Mario Fernando Jiménez, from the School of Engineering, Science and Technology of the Universidad del Rosario.

And at this point they set out the difficulties they have identified in making this not a reality. The main one, they claim, is the difference in time-management logic between academia and industry; that is, the gap between the need to carefully validate the functioning of devices from the scientific method –something that necessarily takes time– and the solutions –usually of an immediate nature– that companies demand. In short, and as usual, the times of science are not the times of the market.

“Companies want ‘for now’ development (and several have taken an interest in our exoskeletons), but we are going at a different speed academically. We have validation phases that we must comply with to ensure that the devices do fulfill their purpose,” says Professor Jiménez.

In their opinion, the costs of technologies, access to financial resources and the challenges they have encountered in the face of the usability of imported exoskeletons are also very important, especially in terms of comfort and adaptation to climatic conditions and the intensity of work in Colombia.

“In Colombia there have already been some cases of importation of exoskeletons that end up archived in a corner just because they are not adapted to our particular needs, especially in the aspects of comfort and sensitivity. It is like the jean, which was born for fishermen and when it arrived to the workers they complained that the fabric was rigid, heavy and produced discomfort in the skin. Over time they softened it and it could be integrated and used by other audiences. Broadly speaking, this happens with exoskeletons: we have to reach a point where with materials we can have versions that are not only adapted to people, but also allow adapting, among other factors, to weather conditions,” explains Castillo.

“The first two causes of loss of life years that can be lived with a disability are related to musculoskeletal injuries. This means that it is a field where many contributions and technological solutions are required and that are accessible to help people stay functional and operational,” highlights Professor Juan Alberto Castillo, from the School of Medicine and Health Sciences of the Universidad del Rosario.

En ese sentido, destacan los retos de diseñar dispositivos aterrizados a las necesidades y características de los trabaja- dores nacionales y la importancia de la sensibilización sobre lo que son verdaderamente los exoesqueletos y su utilidad real para las personas.

Es claro que a pesar de su enfoque inicial en la industria los exoesqueletos tienen aplicaciones más amplias en la vida diaria, como en tareas de acarreo y movimientos comunes que generan fatiga en las articulaciones. Por eso los investigadores Castillo y Jiménez resaltan la preponderancia de desarrollar tecnologías accesibles para todas las personas, especialmente en una población envejecida.

“En 2050 la mitad de la población en Colombia va a tener más de 50 años y va a necesitar ayudas y asistencias. Ese es un campo al que estamos apuntando a largo plazo”, comenta Castillo.

En cuanto al proyecto del exoesqueleto de codo, está en una etapa temprana y aunque hasta el momento los investigadores no han publicado sus resultados en revistas especializadas, ya están creando una primera versión del dispositivo basada en mediciones reales y planean validar su funciona- miento con dispositivos ponibles y pruebas biomecánicas con pacientes. Estas podrían adelantarse a finales de 2023 y proyectan que los equipos se empiecen a comercializar en 2025 o 2026.

Los profesores confían en que este desarrollo colombiano permita bajar costos para que países latinoamericanos puedan tener acceso a este tipo de tecnologías, algo que, sin duda, representaría una revolución en favor de trabajadores y pacientes.