Hunger and malnutrition worsen in Latin America and the Caribbean

By: Amira Abultaif Kadamani

Photos: Ximena Serrano, Milagro Castro

Economics and Politics

By: Amira Abultaif Kadamani

Photos: Ximena Serrano, Milagro Castro

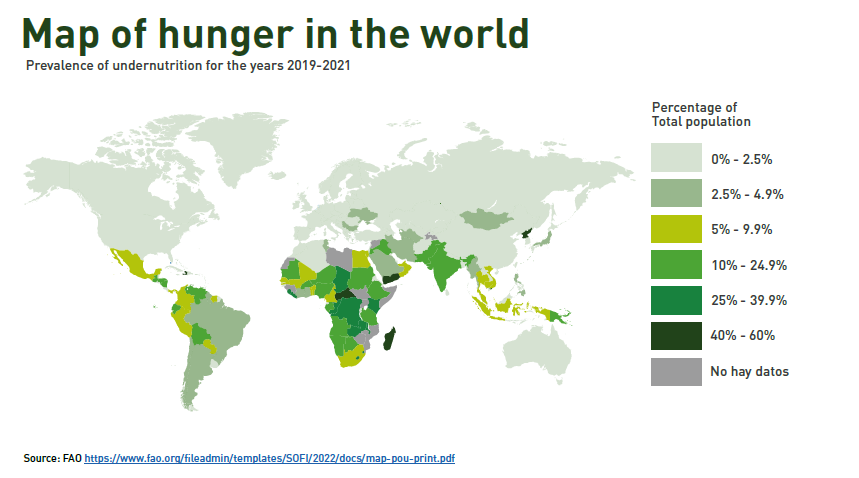

The figures are spine-chilling: around 768 million people around the world suffered hunger in 2021, 46 million more than in 2020, and 103 million more than in 2019, before the outbreak of COVID-19. Those living in Latin America and the Caribbean are 56.5 million, namely, 8.6 per cent of the total population, according to the annual report The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022 (Sofi), published last July by five agencies of the United Nations (FAO, IFAD, Unicef, WFP, and the WHO).

Women and children are most vulnerable to hunger, food insecurity, and the different forms of malnutrition (see glossary). Although those living in rural zones are traditionally most affected, some social groups settled in urban areas have started to be included in the list of victims.

The triggering factors are extreme climatic phenomena, the social and economic conflicts countries face, and the inequalities in different places, a scenario that obviously got worse with the pandemic. If this result is discouraging, it will get worse when the effects of the war in Ukraine are measured.

Food sovereignty refers to the power of a State to create and carry out policies to foster the sustainable production of food items.

These effects have not yet been included in the calculations of the abovementioned balance and will undoubtedly aggravate the setback by altering the world supply chains even more, as well as the price of agricultural supplies and energy. “The world is moving in the wrong way,” warns the document above, and if we continue on that path, we would be very far from meeting the 2030 target set to eradicate hunger, food insecurity, and malnutrition, which is the second Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) out of the 17 objectives set forth in 2015.

Although countries have designed strategies at different degrees and scopes to mitigate and put an end to this dire situation, such objective cannot be met as it is. For that reason, the regional alliances become an important mechanism to accept that challenge.

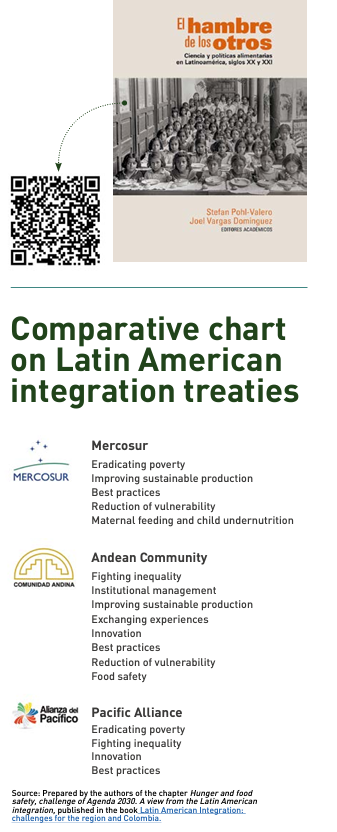

In that line, a researcher from the School of Business Administration of Universidad del Rosario, Alejandra Pulido, together with a group of colleagues from other academic institutions (Cesa, Fundación Universitaria Konrad Lorenz and Politécnico Gran-colombiano), devoted to the task of assessing the policies on food security carried out by different multilateral organisms of cooperation as well as economic, trade, and social development. Such evaluation focused on the Andean Community (CAN), formed by Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru; on the Southern Common Market (Mercosur) with Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Venezuela; and on the Pacific Alliance with Chile, Peru, Mexico and Colombia.

Their work, published as a chapter in the book Integración latinoamericana: retos para la región y Colombia, (Latin American Integration: Challenges for the region and Colombia) edited by Politécnico Grancolombiano (2020), consisted in reviewing the existing literature on this topic and analyzing the official integration documents.

“Our purpose was to see how food security was approached at the community level, and the conclusion is that it was not truly worked upon. What happened mostly, in the context of those integrations, was sharing experiences and transferring knowledge and best practices among the countries,” Pulido affirms. She took advantage of her academic experience in international trade and business to explore the Latin American integration regarding Zero Hunger (SDG #2). “The initiatives in terms of food security are driven by national policies, not by community ones. And although CAN is the organism which has more structured strategies, tactics, and policies, there is a distinction between the proposals set forth (see comparative chart on Latin American integration treaties) and the implementation. As for the latter, a completely different analysis should be conducted.”

As the representative in Colombia for the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Alan Jorge Bojanic confirms that the matter is in the agendas of many entities dedicated to the regional integration, but that convergence of aims, good intentions, and statements has neither been materialized nor translated into allocated budgets or actions. “Except for certain specific policies and agreements, the integration achieved in these stages has been weak; they are important although many times the rhetoric is not translated into actions,” states the Bolivian leader.

The literature examination done by Pulido and her colleagues on food security in Latin America unveiled a prevailing interest of researchers for human health and nutrition topics, especially regarding women, nursing mothers, and children.

One of the great debates hovering this matter is whether countries must tend to food security or food sovereignty. Food security involves guaranteeing both physical and economic access to sufficient and adequate food to cover the daily needs of the population. Food sovereignty refers to the power of a State to create and carry out policies to foster the sustainable production of food items, especially in small scale instead of industrially, embracing the traditional knowledge of communities and the scientific research and prioritizing the local construction of the links for productive chains.

For Pulido, these are not exclusive matters because sovereignty is a means for ensuring security as well. Clearly, all countries do not have the same possibilities and productive capacities and are not competitive in everything. Thus, a balance between self-sustainability and foreign trade exchange has to be sought for the sake of gearing towards synergies and achieving more efficacy and efficiency when it comes to fighting hunger and food insecurity.

“Thanks to sovereignty, production and exports are controlled, a better coordination with suppliers is achieved, and different productive mechanisms are generated. But that does not mean being completely self-sufficient, since that is very hard today. What can be actually achieve? based on food sovereignty, better mechanisms for self-sufficiency are generated for people who don’t have access to food,” the researcher asserts while underlining the value of integrationist processes and the complementary nature of national economies.

“The concept of sovereignty is very arguable (…) because some people associate it with import substitution (…) and others soften it by speaking precisely about how to avoid dumping in the national production that may affect the food security in the country,” Bojanic clears up. He emphasizes that the phrase that prevails in the FAO is food security, with an additional adjective, “nutritional” because one thing is to fill the tummy and another is to be well-nourished. As he sees it, both concepts can be complementary, as long as countries work to guarantee the good feeding of their people and, simultaneously, strengthen production and national products, without becoming a limitation to importing indispensable food for their inhabitants.

In Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), there are many organizations for regional integration, including the above mentioned and others like Celac, Aladi, Alba-TCP . One could think that such a diversity of organizations diminishes the weight, the force, and the efficacy of the process that seeks effective solutions, if we are “struggling” along different roads towards a common goal. However, Pulido considers that such a situation may not necessarily happen because these bodies have diverse and complementary objectives, which does not hinder achieving a convergence among them in order to meet the ultimate target of the SDG #2. And, since we live a global world, the need for interconnection is, on many occasions, evidently unavoidable.

According to a study made by FAO, OPS, WFP and Unicef on food and nutritional security in LAC in 2019, “the periods with greatest economic growth [in the region] during the last decades coincide with the most important periods of hunger reduction. (…) Therefore, the economic deceleration of the countries in the region is one of the factors most affecting food and nutrition security of people and homes, with different consequences in the diverse population groups. This is especially meaningful for a region with high levels of inequality.”

“Our purpose was to see how food security has been approached at the community level, and the conclusion is that it was not truly worked upon. What happened mostly in the context of those integrations was sharing experiences and transferring knowledge and best practices from each country,” professor Alejandra Pulido states.

Colombia is leading as the country in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) with greatest economic development in the region , with a projected GDP of 6.1% for 2022, above the world growth average of the member countries. That is the harvest of the economic reactivation implemented up to now, and is a good indicator. But, in Pulido’s view, that is not a solution for food insecurity. “Having a higher growth this year due to a reactivation process does not imply that we can guarantee, in a certain period of time, food security, as there are other variables which, instead of drivers, are limitations,” she warns, referring mainly to agricultural-industrial supply overcosts, which are transferred to the family basket. “Growth may occur, as in our case, by industrial production or hydrocarbon exports, and the inter-annual variation of the GDP does not determine food security,” she adds.

The FAO representative in Colombia agrees on the existence of a relationship between economic growth and poverty reduction, but he clears up that that happens only if there are specific programs aimed at such a purpose. “Economic growth will not occur if it is not accompanied by a wide base growth, namely, there are many factors involved in such a growth and that, in turn, a good deal of those earnings is geared towards poverty eradication programs.”

Pulido believes that Gustavo Petro’s incoming government has shown new policies on agricultural transformation, which could enhance the food scenario. Nevertheless, that process will not bear fruit in the short term, and its benefits will not be harvested before 10 or 12 years. In addition, the availability of raw material should be assessed, just as the production costs of local supplies and the supply chain compared with import costs for agricultural supplies or products.

As the Sofi report states, the world dedicated almost 630,000 million dollars a year in the 2013–2018 period to support feeding and agriculture, fundamentally to individual farmers, by means of policies on trading and markets, and state subsidies. But, “mostly, this support not only alters the market but it is not reaching many farmers either, it damages the environment and does not foster the production of nutritional food,” warns the document. This happens because “the assistance to agricultural production is mainly focused on basic food, dairy items, and other products rich in animal proteins, especially in countries with high and mid-high incomes. Rice, sugar, and diverse types of meat receive most of the incentives at the global level, unlike fruit and vegetables, which get less support in general, or they are even fined in some low-income countries.”

For this reason, one of the key messages from the multilateral entities that conducted this analysis is that state subsidies must be directed to consumers instead of producers since that means an evident improvement in the accessibility to a healthy diet, with a good side effect: the reduction of greenhouse gases in agriculture.

However, that is not a magic formula because the report immediately alerts about the “likelihood of undergoing negative consequences in the reduction of poverty, the farming incomes, the total agricultural yield, and the economic recovery.”

The big question that such a scenario poses is how the public resources dedicated to agriculture can be used to meet multiple objectives, how to foster production and make a transition towards a more efficient decarbonized agriculture, which may utilize less resources and protect the soils and simultaneously fight compelling needs, such as the reduction of poverty. “These multiple objectives are sometimes contradictory and that is where politics steps in, which, as the saying goes, is the science of what is possible, not of what is desirable,” Bojanic points out.

In the middle of this entangled labyrinth, we still need to consider the implications of a soaring world inflation that begins to look like a recession. The challenges to overcome are enormous, and there is no detailed model that may be applied strictly by all countries suffering from hunger or food insecurity because in the specificities of each of their societies, there are unique advantages or limitations. However, faced with a shared set of problems, the countries in this region of the world could, at least, go beyond their positive experiences to build synergies that mitigate this painful reality.

-Food insecurity: “Situation in which people cannot have regular access to sufficient innocuous, and nutritive food for a normal growth and development, and to lead an active and healthy life.”

-Malnutrition: “Abnormal physiological condition caused by insufficient, unbalanced or excessive macronutrients contributing to food energy (carbohydrates, proteins and fats) and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals), essential for growth as well as physical and cognitive development. It is manifested in many ways, such as: undernourishment and undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies, overnutrition and obesity.”

-Undernutrition and undernourishment: “When food intake is insufficient for satisfying the needs for feeding energy.” In Colombia, there are 4.4 million undernourished people according to data from Sofi 2021.

-Micronutrient deficiency: “when one or more vitamins or essential minerals are lacking. They are measured in milligrams or micrograms.”

-Overnutrition and obesity: “an abnormal or excessive accumulation of fat that may damage health. Overweight is one of the indicators of malnutrition in girls and boys under 5. It is estimated that 4 million girls and boys under 5 are overweight in Latin America and the Caribbean, constituting 7.5% of the infant population in the region.

Sources: https://www.fao.org/hunger/es/

FAO, OPS, WFP y UNICEF. (2019). An overview of food and nutritional security in Latin America and the Caribbean 2019. Santiago. 135. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO