´The Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta (Great Swamp of Santa Marta) urgently needs a right considers the relationshps between people and nature´

By: Michelle Soto Méndez

Photos: Milagro Castro, Andrés Gómez https://doi.org/10.12804/dvcn_10336.42363_num7

By: Michelle Soto Méndez

Photos: Milagro Castro, Andrés Gómez https://doi.org/10.12804/dvcn_10336.42363_num7

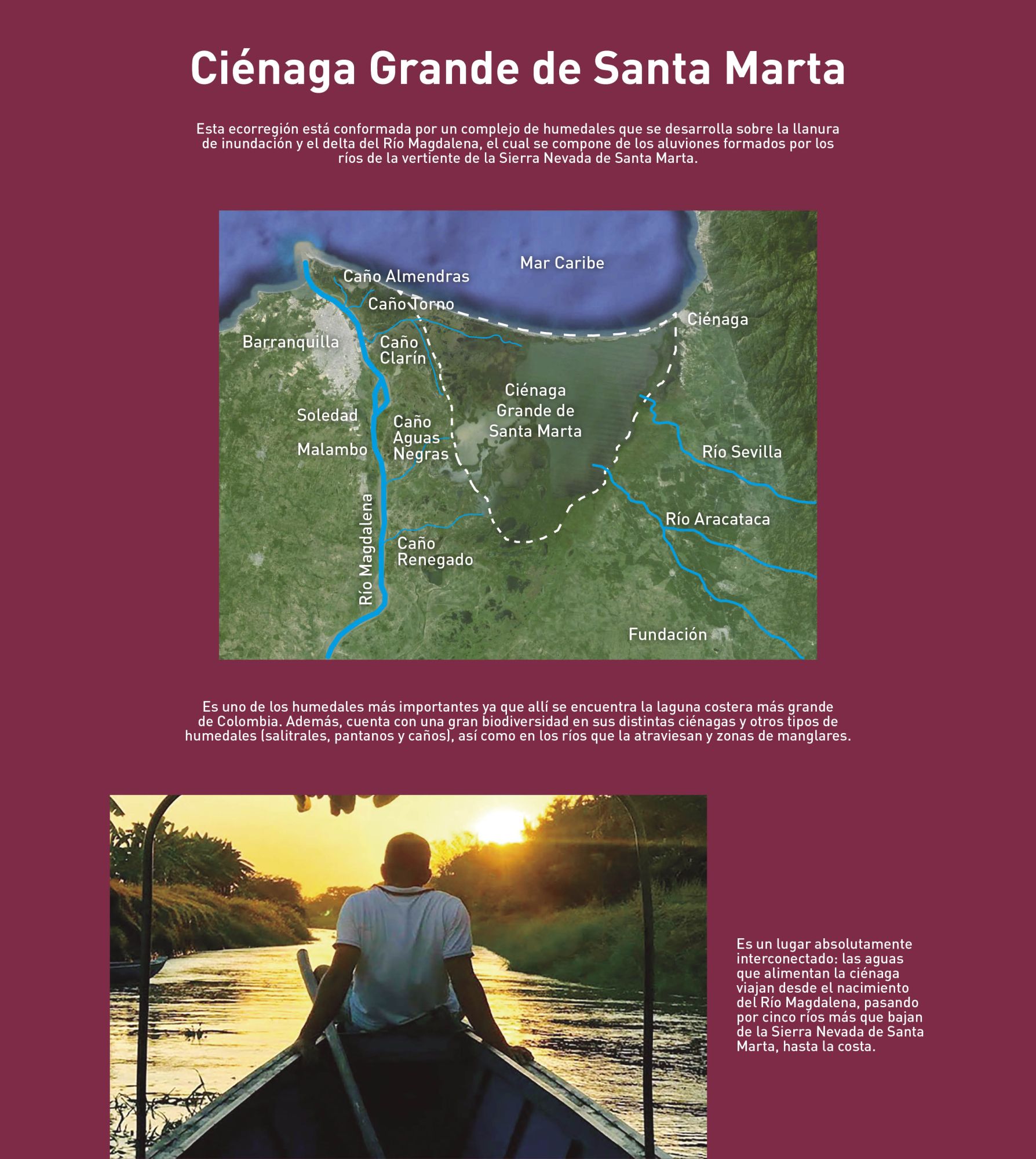

I the Caribbean, just to the north of the country, the intersection of fresh and salt waters leads to a very particular wetland, which is even considered to be of global importance. There, in the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta (Great Swamp of Santa Marta), life is possible thanks to that ecosystem dynamic that shapes people.

“People have very particular relationships that they have built over time with the swamp. They have a relationship with fauna and flora that goes beyond just food; it is a relationship of conservation, but at the same time of recreation and protection. Of course, it is not environmental protectionism; I am talking about a way in which the daily lives of people seek to conserve an environment while also having a dignified life”, says Andrés Gómez Rey, environmental lawyer and professor of Universidad del Rosario.

“Law does not understand that. The law understands that there is an ecosystem and a person; then it protects them, it creates a regulated scheme to protect the two things, but it oes not see that there is a relationship between them. Hence, the law splits the elements, but does not show that everything is interconnected, that we are all part of a network. That is the big problem with the swamp,” he continues.

Many things happen in the swamp, all at once. The different categories of environmental protection and management (such as being a Ramsar wetland –an internationally important wetland included in theRamsar Convention list- and UNESCO's biosphere reserve, among others) overlap with the ancestral and traditional uses (such as fishing and sacred sites) of the communities in the area. Moreover, because everything is interconnected by water dynamics, actions carried out in a certain part of the territory may infringe upon another community’s right to a healthy environment

Andrés Gómez and Gloria Amparo Rodríguez, researchers and professors in the Faculty of Law at Universidad del Rosario, together with Álvaro José Henao, lawyer and legal adviser on environmental issues, wrote an article published in the journal CIBOD d’Afers internacionals (2022), in which they analyze the legal tools that have been used for the protection of the Great Swamp of Santa Marta. Researchers found that the application of these laws has generated tensions associated with guaranteeing human rights, the wellbeing of people and the preservation or rights of ecosystems

"What the Court orders is ‘do this to curb pollution and do this to do something else’; but those orders, anyway, are fractional, have conservationist logics, harm people and encourage struggles,” comments Gómez. “The article shows a little bit the anguish of how judges sometimes do not understand what people are going through and take action for what is called resources, not territory, or in favor the people. And they always prioritize what has discriminatory effects or privilege other species or other actors (often economic ones). Thus, judges may end up accentuating or exacerbating the conflict,” the academic added

"If there are no democratic consolidations around how to manage our own culturally appropriate territories, then these legal rules in the abstract are not going to work. And every place is different. Each is an absolutely different world and creates different relationships."

In an interview with the Advances in Science Magazine, environmental lawyer Andrés Gómez clarifies the choice and shares the most relevant concepts about the initiative that he and his co-authors are proposing as a solution

DC. This vision centered on the natural resource that, seeing it from the historical perspective, could have been valid at the time, falls short of the present we live in. Are we moving towards a more comprehensive view of the landscape?

AG.Environmental Law failed profoundly for many reasons, but above all because by fracturing the components and because of the existence of other problems derived from the legal architecture, we have not been able to halt the planetary crisis. That fractional logic has caused Colombia to destroy one part, while protecting another. Now, a place has a lot of things and around those elements, relationships are woven.

I think that there is a necessary shift in the transformation of what is called Environmental Law, and that change seeks precisely to understand these relationships. I think that recognizing that everything is interconnected, that there are interrelationships, assemblages and respect for the networks that are built naturally is something very beautiful.

Of course, transformation involves new categories. For example, in Colombia, we must conceive of the territory as a more complex relational environment; that would serve to show that the planet is claiming to be an actor in the debates. So, the judges have to argue that the river and the mountain are actors in the judicial debates and that they have a force that can modify the situations; that this is not a matter of technically doing things, but that science has a political component and the norms have an intention that is sometimes hidden

I believe there is a loud call for a reformulation, and the article we published is going somewhat in that direction. The article aims to make visible that the Law prevents us from seeing the political content of science and the agendas that are behind the norms and technical production, among other aspects. A case like that of the Great Swamp cannot continue under that logic; there is a lot of pollution there, people are suffering a lot, species are dying. So, if there is no change in logic, then this will not work…

DC. Is there a possibility of conceiving of territory as a space to make visible these relationships that exist between ecosystems and people, where both the rights of nature and human rights are respected? At the end of the day, our worldview –as people– is very much tied to those relationships we establish with the environment.

AG. I totally agree. I think Colombia is seeking, at least from academia and social sectors, to rethink the traditional categories; to stop talking about resources and start talking about territory, because, in addition, the word resource implies a use and that obeys a very commercial vision, as if we were talking only about raw materials

A beautiful initiative that Colombia has embraced the rights of nature, which have tried to break the limits of law and other disciplines in order to understand a territorial vision and a world located in the space in which it exists to understand these dynamics. Although that is the goal, sometimes it is very difficult to fight against the law, because the challenges are not necessarily legal

To include the territory as a category, a lawsuit is not filed, rather, a multitude of extralegal strategies are used to insert it into the legal system or begin to convince operators of the importance of breaking the traditional categories. And those processes are historically long. Of course, that is why Colombia has many opponents of the rights of nature. There are always people who find it absurd or simply do not understand the dangers, and that is why they want to halt it.

A beautiful initiative that Colombia has embraced is the rights of nature, which have tried to break the limits of law and other disciplines around understanding a territorial vision and a world located in the space in which we are to understand these dynamics, says Professor Andrés Gómez Rey from Faculty of Law.

DC. If the territory gives visibility to both ecosystems and people, as well as to their interrelationships, that could also help reduce tensions. It could even relieve the state of some weight regarding conflict resolution, right?

AG. Sure, that is the crux of the matter. When I talk about ecosystems, I mean all the intersectional species that bet on their own survival and a dignified life. However, when talking about the human being, it is often decontextualized and this makes judicial and legal decisions very problematic. Now in Colombia, all regulations have an immense democratic deficit, which causes that when this is transferred to cultural places, the norm is rejected.

If there are no democratic consolidations around how to manage our own culturally appropriate territories, then these legal rules in the abstract will not work. And every place is different. Each is an absolutely different world and creates different relationships.

DC. However, by dignifying people and ecosystems, we are empowering people to take ownership of, and thus have a relationship with it. In the end, that relationship with the territory is what leads to its care.

AG. And we take care of each other. The beautiful thing is that the people in those places understand how important it is that everything exists so that we all can exist. The sociologist Norbert Elías speaks of “figurations.” He states that figuration is the relationship that we have historically built with everything around us and that together we try to protect; he argues that they are “relative relations” because we want to be better relatives.

DC. Listening to you reminds me of the concept of collective care used by feminist collectives and environmental defenders. I think that we also have this care with nature: as a human being, I take care of her and she takes care of me through ecosystem services.

AG. I have two personal commitments. One is a community and popular right that has to be built between state and social bases so that effectively all rationalities and ways of seeing the world that can be present. The other is the existence of a relational constitutional right. These concepts can expand our understanding of democratic and relational needs, at least in environmental matters.

DC. In the Worldviews and Governance of Indigenous Peoples, Could We Find Elements That Enrich This Relational Vision We Are Discussing?

AG. I think they are the ones who have invested the most on that. What happens is that we have not been able to understand it. The indigenous peoples in Colombia are the ones who have told us the most, and for a long time, that this is not a matter of subject-object, but of relationship, of history, of construction between all. I think indigenous contribution is vital, and we need humility, respect, to understand what they are really communicating to us for a long time.

DC. While we are discussing about the Great Swamp of Santa Marta, I feel that, equally, we could be talking about any landscape of Costa Rica, Ecuador or Peru. In other words, this is a Latin American issue as such.

AG. I consider it that way as well. This is much broader than what we are currently observing. I believe that this commitment to have a Latin American relational manifesto that has a political strength is still under construction. However, I also believe that we do not believe it. The strength is there, but we lack confidence.

DC. It seems to me that this article is definitely an invitation to talk.

AG.The article is written to engage with formalists and uses that language extensively; however, it is designed to plant a seed as an idea. Let's see if we can suddenly transform a little bit of traditional Colombian environmentalism, at least.

Rights of nature

Although many countries have raised the right to a healthy and ecologically balanced environment to constitutional status, this is focused on one of the subjects – the human being – and leaves it to the interpretation of the operators of justice whether this right also extends to other species (for example, the jaguar) and even to ecosystems (a river or a mountain). One of the first to put the issue on the table was Christopher D. Stone, professor of Law at the University of Southern California (USA),when in 1972 he wrote the essay ¿Should trees be legitimized? Towards the legal rights of natural objects.

Likewise, in the 1970s in South America,Godofredo Stutzin already spoke of how “recognizing nature as an entity endowed with rights is legally possible, takes into account a real situation and responds to a practical need.” This is how a new paradigm in law begins to take shape, one that encompasses nature in its entirety and is opposed to the classic anthropocentric vision, in which, although there is supposed environmental protection, this is based on utilitarian reasons.

Precisely, with this desire to modify the anthropocentric paradigm, recent initiatives have been developed in Latin America to grant rights to nature, among them, ahabeas corpus a una orangutana(as happened with “Sandra” in Argentina) or a bear (“Chucho” in Colombia). There have also been movements to recognize an ecosystem as a subject of law; as happened with the el Río Quindío, in Colombia.

Others have gone a step further. In 2008, Ecuador granted rights to nature in its Political Constitution, whose article 71 says: “Nature or Pacha Mama, where life is reproduced and carried out, has the right to have its existence and the maintenance and regeneration of its vital cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes fully respected”.

Although the examples given above are from Latin America, the rights of nature have also been made official in other countries such as Australia, New Zealand and India

Ecosystem services

People benefit from a range of services provided by this ecoregion, including:

- Environmental regulation services: protection from natural phenomena, water purification, sediment and nutrient retention, aquifer recharge, and carbon dioxide capture..

- Provisioning services: fishing resources for food, production of goods and natural fibers, crops of some foods, and small livestock, which are exchanged in local and regional markets

- Cultural services:gastronomic variety, such as mote de guineo, carimañolas, empanadas, arepas, buñuelos, or sancocho de costilla and mondongo; tourist activities in search of palafitte cities, such as Nueva Venecia; collective stories and narratives, such as that of the “house of the devil” in the municipality of Ciénaga; or the interest of social scientists in the appropriation and creation of indigenous technologies, such as the “bongaducto”, a small boat that transports fresh water for human consumption, from the mangroves to the saltwater areas.

The people of the swamp

This is an ancestral territory where four indigenous peoples live: Arhuaco, Kogui, Wiwa and Kankuamo. According to their worldview, they are called to be guardians of nature and for this reason they promote the protection of the “black line” in their ancestral territory, known as Umunukuno, which means the heart of the world

There are also peasants living there, whose relationship with flora and fauna has fostered a series of local and traditional knowledge. There is a cultural interdependence with the ecosystem to the point that, without the swamp, they would be destined to disappear

The threats

The Great Swamp is not exempt from environmental problems:

-It still bears the consequences of a series of historical impacts, such as the construction of roads in the late 1950s, which led to the reduction of the exchange between the lagoon system and the sea, as well as between the Magdalena River and its delta.

- High levels of pollution resulting from local anthropic activities and those generated in other parts of the territory, although, due to water dynamics, they are concentrated in this ecoregion.

-Siltation of the canal system due to deforestation, the blocking of caños to control emissions, and the draining of smaller wetlands, with the consequent effort to prevent the salinization of crops, has resulted in a decrease in the supply of freshwater that the wetland previously provided.

-Low coverage of basic services, especially aqueduct and sewerage, which means that solid and liquid waste from coastal municipalities have as final destination the Magdalena River and even the swamp itself

“The degradation is not only ecological, but also social, as the human settlements there suffer a precarious situation in terms of well-being, which is paradoxically aggravated by the ecosystem deterioration that affects fishing, food production (food security) and access to drinking water.”.

Excerpt from the article written by Andrés Gómez, Gloria Amparo and Álvaro José Henao and published in the magazine Cidob d'Afers Internacionals (2022).