The hyperconnected generation

By: Magda Páez Torres

Photos: Alberto Sierra

Society and Culture

By: Magda Páez Torres

Photos: Alberto Sierra

Have you ever thought about how many times a day you check your smartphone? Undoubtedly, smartphones have become part of our everyday life, to the extent that in Spain, according to a study conducted by researchers at Hospital General Universitario de Valencia in 2018, people checked their smartphones 150 times a day. The Digital 2022 Global Statshot report stated that in Colombia, a person spends an average of 3 hours and 46 minutes facing the cellphone screen, connected to social media.

That is because these devices combine the chance of communication with several entertainment options, shopping, and accessing information in real time. All of this has led this generation, especially children and young people, to adopt an online lifestyle, where being connected seems to be more than a necessity.

How dependent has contemporary society become on smartphones? What are the consequences of the close and continuous use of these devices?

Precisely within the framework of these questions, Professor Óscar Robayo Pinzón, of the School of Business Administration of Universidad del Rosario, together with a group of researchers, published the study entitled El uso excesivo de teléfonos inteligentes y aplicaciones nos hace más impulsivos? Una aproximación desde la economía del comportamiento.( Does the Excessive Use of Smartphones and Apps Make Us More Impulsive? An Approach from the Point of View of Behavioral Economics).

From the point of view of behavioral economics, a discipline that seeks to understand the effect of emotions and psychological biases on economic and financial decisions, academics set out to assess the relationship of young people with their smartphones: frequencies, preferences, and motivations or impulses to stay connected. “What we found is that there is a correlation between making impulsive decisions and a greater dependence on smartphones, perceived from the users,” remarked the researcher Robayo. That is to say, there is a pattern of impulsive selection when it comes to using the cell phone, characterized by obtaining immediate positive actions such as likes, views, or reactions from other users.

The study was conducted with 20 students for 28 days. Through an application valid for Android and iPhone, the usage time of the apps was monitored individually for each of the 20 participants, resulting in 560 logs collected on a weekly basis. The researchers did not have direct access to the devices, only to the Excel reports generated by the app.

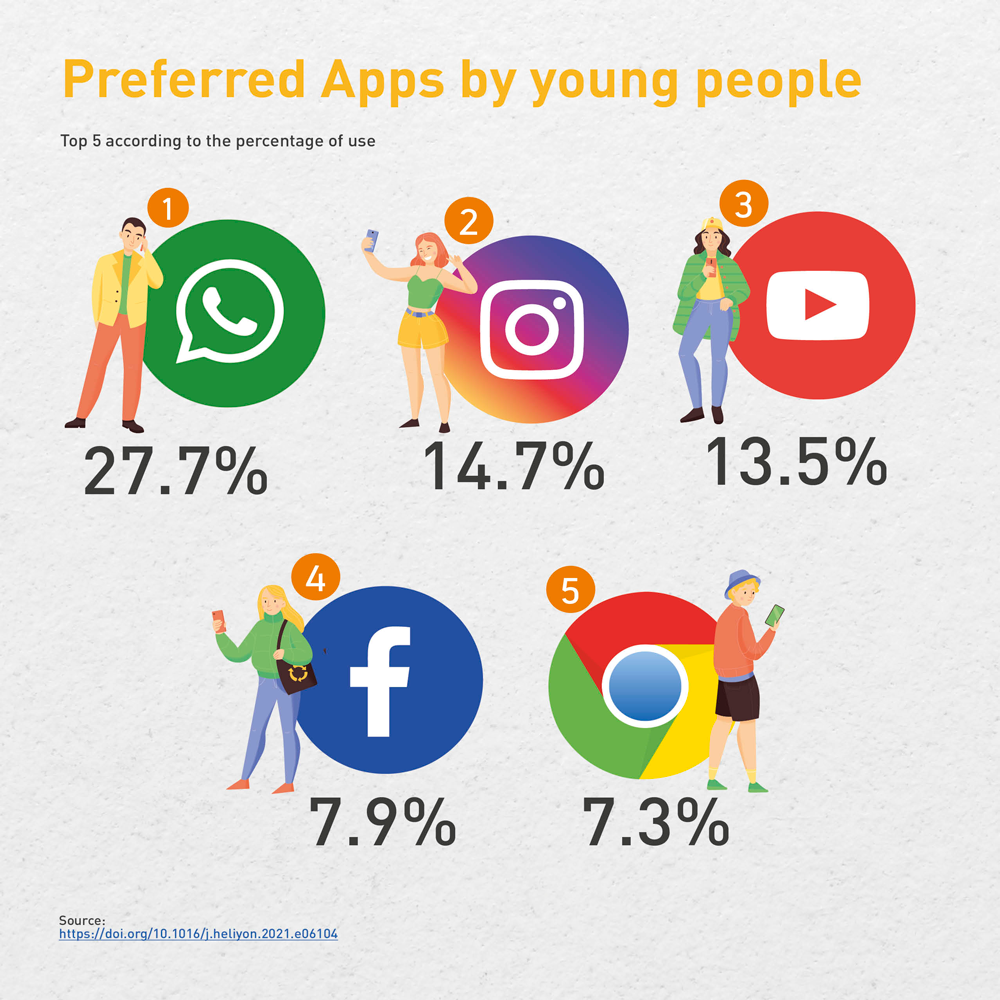

The consolidated log showed a total of 619 different applications, with an average of 68.6 apps installed on each device. A detailed analysis showed that the most used apps by the participants were WhatsApp, with 68.88 minutes per day; Instagram, with 36.64; YouTube, with 33.64; Facebook, with 19.53; and Chrome, with 18.20 minutes on average. It is important to point out that this record was taken prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the use of mobile devices skyrocketed, which may have changed the usage habits of the apps.

The study results show that people who are more impulsive prioritize the use of smartphones without realizing that this may have negative consequences in the medium term, which stems from the normalization of phone use in working, academic, and family spaces.

“It seems that it’s okay for you to check your smartphone many times a day, and no one socially punishes you for it. As a result, people check their phones between 90 and 150 times a day, depending on the country and where the tracking comes from. Every time we check our phone, we may be a bit impulsive, i.e., we can’t help checking it every time it vibrates, every time a notification rings; it’s the impulse to see what happened, who contacted me,” says the expert.

This statement is complemented by Sandra Rojas, a professor at the Universidad Nacional, who was also part of the research team. “The prolonged use of any source that may cause a habit is going to increase the probability of acquiring an addiction and making it more difficult to leave; for example, addiction to gambling, to food, to alcohol, to drugs… The only difference is that the use of virtual networks is socially accepted. Therefore, what we tried to show in the study is that although nowadays it is necessary to have a social network or to use a smartphone, it somehow generates greater impulsivity and addiction to use. The more time you are exposed to the stimulus, the more addictive it will be,” she explains.

This is precisely what young people from different backgrounds account for. For Juan Carlos*, a high school student, the smartphone has become part of his routine. “I use it all day long. If I could, I’d be online 24 hours a day, because it’s a form of entertainment for me. My life would be awful without my cell phone, because it distracts me. I can chat, do many things,” says this teenager, whose favorite apps are Instagram, Tik Tok, Facebook, and WhatsApp.

Laura Valdivieso*, a university student, holds a similar opinion: “The cell phone has a great influence on my life, in the sense that I work ‘there’, I am in contact with important people to me and I also socialize. So, this device is essential in everyone’s life because it means being in contact with someone without actually seeing him or her every day,” the young woman emphasizes.

They are part of the 81.3 per cent of the total population that uses social networks in Colombia, that is, 41.80 million people, according to 2022 da ta from DataReportal.

Different studies have also delved into the potential consequences or collateral impacts from the prolonged use of smartphones, as was contextualized by the research conducted by Professor Robayo. “In many countries, there seems to be a link between a high use of social network applications and negative consequences for the wellbeing and health, such as insomnia, anxiety, depression, and self-esteem and self-image issues in teenagers and young adults. There is a dissociation of one’s own body image to the extent that these young people are more exposed to these filtered contents,” says the Rosario researcher.

Another key point addressed by the research is the fear of being disconnected from virtual reality. “In addition to whether or not I have likes or views, there are new constructs such as nomophobia, i.e., the phobia of not checking the phone or the phobia of not having a cell phone; the fear of missing something that is happening on the networks,” (FOMO, fear of missing out) explains the researcher.

For example, in a recent study by the same team of researchers, which is currently under peer review, an experiment in which fictitious rewards were used to evaluate the behavior of users was conducted. The users were offered money in exchange for spending less time on their social networks. “Something like, Would you stop using your social networks for 30 minutes, if you got 1,000, 2,000, 5,000... Colombian pesos? In effect, as we reduced their time on social networks, they asked for more money in return.”

“We found there is a correlation between making impulsive decisions and a greater dependence on smartphones, perceived by the users”: Óscar Robayo Pinzón, professor at the School of Business Administration of Universidad del Rosario.

Faced with this scenario, the imperative question is which solutions do we have at hand. In this regard, researcher Óscar Robayo proposes self-regulation. “There is no clear solution because there is no social recognition of the fact that something is going on. The situation has been normalized, even more so since the pandemic, which accelerated the adoption of platforms, allowing us to be connected and continue working. My option would be to conduct a kind of self-regulation, as is practiced with environmental issues where there are incentives to use fewer cars and promote the use of bicycles. We have to think that the change starts with us, to be self-conscious about not using the phone, to use it a bit less in exchange for incentives,” he said.

Similarly, researcher Sandra Rojas called for family to set rules or agreements to regulate the use of cell phones. “When it tends to become obsessive, compulsive, or addictive, a habit can be controlled in the core of the family, for example, by creating rules, especially in shared moments: dinner, breakfast, or those spaces where a dialogue should prevail.

It is a matter of agreeing on rules to avoid the use of social networks, or the telephone itself, and to be present in the here and now,” she says. Although at the level of governments and legislation the road is even longer because of the implications this has in terms of individual freedoms, academics agree that it is necessary to look for options to gradually encourage disconnection in certain environments, with parallel stimuli, so that people gradually regulate the use of mobile devices by personal choice and so that the online generation can take a break and address the demands, benefits, and challenges of a tangible reality.

*The names of the students were changed since they are minors.