Colombian Schools Renew to Welcome Venezuelan Migrant Children and Adolescents

By: Lina María Leal Villamizar

Photos: Alberto Sierra, Milagro Castro DOI https://doi.org/10.12804/dvcn_10336.42349_num7

Society and Culture

By: Lina María Leal Villamizar

Photos: Alberto Sierra, Milagro Castro DOI https://doi.org/10.12804/dvcn_10336.42349_num7

“They left him like a liver,” Andreina Gutiérrez says of her 13-year-old son Ángel, who was bullied at a district school in Bogotá last year. As he remembers it, the boy remained silent and distressed that afternoon until his older sister, as she hugged him, noticed a bruise on his neck. This would be the zero point of a map of bruises along the back up to the legs, caused by real days of ‘kicking’ that a group of sixth graders had been giving the child.

Andreina and Ángel arrived in Bogotá during the pandemic. They came from Ureña, a city of 38 000 inhabitants located in the border area of the state of Táchira, from where hundreds of people migrate every day in difficult economic situations and where, in addition, there are frequent clashes over the dispute of the territory between guerrillas and paramilitaries. “The children were growing up in a place where they suddenly put an explosive. That’s why we came … and my brother just arrived with his son, because very close to the house where we lived they put a grenade and a whole family died,” Gutiérrez says.

In Bogotá, the father of Andreina’s children had managed to set up a plastic bags micro-enterprise, so the family saw the opportunity to work and settle in the city. In a short time they obtained a place for Angel in one of the 386 public schools, but the child had difficulty adapting as he presented attention deficits and short-term memory issue. In addition, almost everything was different: accents, flavors, smells, sounds and landscapes that mixed in the cold ‘concrete jungle’ with almost eight million inhabitants, so far from their hometown.

Without paying attention to it, Ángel went every morning to the institution, confident that he would soon be accepted by the sixth grade group, while asking that they no longer call him “veneco”, as many refer to him and other comrades from the border country in a derogatory way. One day, in the midst of a heated discussion, the beatings began among the children of the course, which ended with several bruises, silences and the subsequent expulsion of two of the aggressors.

The study found that at the first level, that of the Ministry of Education, the magnitude of the migratory phenomenon is recognized, but at the same time it is assumed that it can be responded without major changes...

“Then they decided to close and close the case,” Andreina says, adding that after the episode her son has required support from psychologists, teachers and family members. One of Ángel's counselors, Martha Villamizar, says that although bullying occurs in school among all types of children, it is true that Venezuelans are victims of the practice more frequently: “Some of the migrant children are not at the same academic level and therefore find it difficult to adapt; others are very introverted or on the defensive. That is, any situation or condition serves as an excuse to increase rivalries. In these cases we implement restorative practices through which we work on socio- emotional education and competences such as empathy, key to understanding the situations that these migrant children go through and welcoming them more easily.”

WHAT IS BEING DONE IN THE COUNTRY TO WELCOME CHILDREN LIKE ÁNGEL?

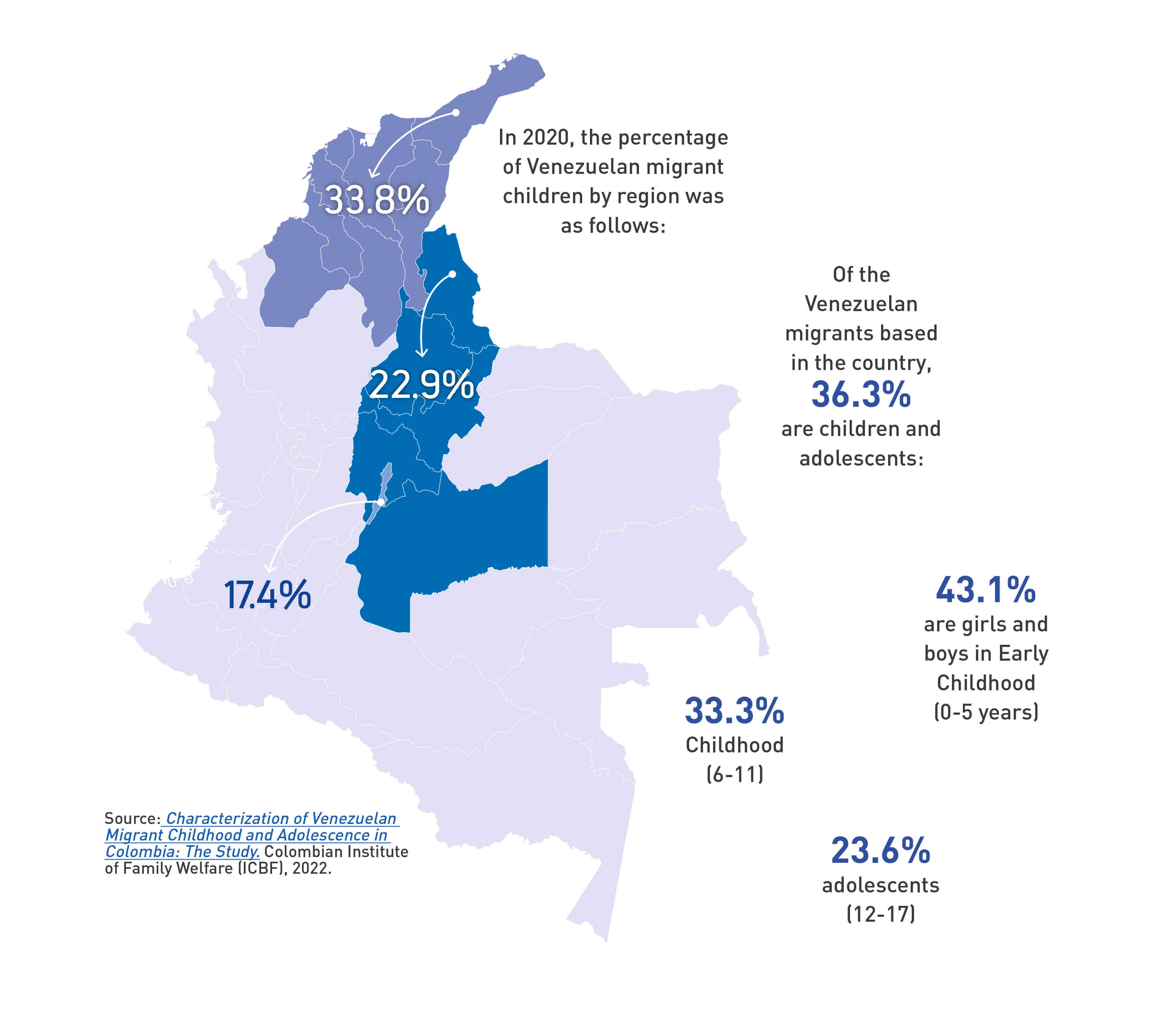

Colombia has become the world’s largest recipient of Venezuelans, opening doors – whether as a crossing or residence – to more than 5 million Venezuelan migrants between 2012 and 2022, according to data Reported by Migration Colombia. By September 2021, there were about 1.8 million Venezuelan migrants based in the country. Of these, about 36.3 percent were children and adolescents.

In 2021, sociologist and doctor Nathalia Urbano Canal, from the School of Human Sciences of the Universidad del Rosario, joined the project “School and Migration: Responses to the Educational Needs of Venezuelan Migrants in Three Subnational Governments of Colombia”, led by Professor Claudia Díaz Ríos, from the University of Toronto (Canada) and who focused on the issue of Venezuelan migrant minors by asking about the ways in which their educational needs were understood, interpreted, and addressed in Colombia. This inter-institutional partnership has expanded the scope and resources for research.

“We wanted to find out several things: how do actors in the education system interpret and implement the integration of Venezuelan migrants into the regular education system? What factors shape these interpretations and applications? And how do different actors’ interpretations affect the responses migrants receive from the education system?” explains Urbano and Díaz, adding that the variations and difficulties generated by Covid-19 added to these questions.

Professor Nathalia Urbano, from the School of Human Sciences of the Universidad del Rosario, concludes that “in general, there is a great sense of isolation among schools, especially teachers, to generate responses that integrate this population into the educational system. Ultimately, it is the teachers who are challenged to integrate the migrant population adequately into the education system. For me they are the heroes and heroines of this situation.”

What about education?

According to an ICBF study (2022), based on data from the Dane, this population has a school lag rate of more than 72.9%. The maximum age of the group, which is 17 years, was 2.6 years below educational attainment for the age. 27.5 percent of girls, boys and adolescents are outside the education system, and 20 percent of those who are not studying said that the reason for the lack of attendance was because they had to move from their usual place of residence. In addition, during the pandemic, more than 90% of migrant children and adolescents did not use devices such as a desktop, laptop or tablet computer, and 35% did not have access to the internet.

Source: Characterization of Venezuelan migrant children and adolescents in Colombia. Colombian Institute of Family Welfare (ICBF), 2022.

The team contacted various actors from entities working with the Colombian education system where the majority of Venezuelan migrants were based, that is, the capital district and the border areas of the departments of Norte de Santander and La Guajira. They also selected schools in each location, taking into account the five schools with the highest number of Venezuelan children enrolled. “The pandemic gave us the opportunity to have many people to want to talk, so there were no problems in getting the selected entities and directors to talk to us,” Dr. Díaz says.

The researchers conducted more than 200 virtual interviews with Ministry decision- makers and Education secretariats, representatives of cooperation organizations, managers, teachers, counselors, family members and students. The word about what they were doing was spreading and growing like a “snowball” and more people interested in participating in the project was attracted.

Professor Urbano recalls that “we had difficulties, above all, to carry out the interviews with the children (none under 13 years old and always with the consent of their clients), because some felt embarrassed, were unsure about the purpose of the investigation or the reason for the contact, and many did not have mobile data or the internet access to conduct the interviews. We invested resources so that they could have what they needed.”

In this regard, Dr. Díaz acknowledges that there may be a bias in the responses of minors as they are suggested by teachers, and “we know that these tend to recommend outstanding students. Even so, we collected very rich information and found stories of great resilience.”

THE CHALLENGE OF CLASSIFYING DIVERSE AND DISARTICULATED RESPONSES

The teams from Colombia and Canada systematized and analyzed the interviews conducted in what is called a ‘vertical study’, identifying three levels of influence in the process of building-developing responses to meet the educational needs of Venezuelan children and adolescents. At the top of the structure is the national level, that is, the Ministry of Education; the second is the territorial level, with the secretariats of Education of Cúcuta, La Guajira and Bogotá; and in the third level are the schools. This classification also took into account an important actor: multilateral and International Cooperation organizations.

The study found that at the first level, that of the Ministry of Education, the magnitude of the migration phenomenon is recognized, but at the same time it is assumed that it can be responded without major changes, given the decreasing demographic trend of the national population of school age that has left a remnant of capacity and, consequently, a good part of the migration is considered temporary. “Although the right to education is guaranteed, there is the idea that the integration of the Venezuelan population into the education system is equivalent only to giving them access to it,” says researcher Urbano, who emphasizes that access constitutes only part of integration, but is not enough.

At the next level, that of the secretaries, they found variations in how the educational needs of this population are met. In Bogota, the territorial entity that receives the largest number of migrants operates, but at the same time the one that has the most school quotas. “The capital had no problem providing access to this population. They had sufficient conditions to counteract the risk of overuse of children in a classroom,” says Urbano, adding that no additional strategies for integration were generated, nor was there a close work with international cooperation agencies.

In La Guajira and Cúcuta, the secretariats have limited capacity to attend to Venezuelan migrants, and international organizations play a significant role, providing aid such as food and school supplies. There is also an interest on the part of the secretariats and schools to know the subject, as well as more familiarity with the travelers, since when living in border areas the dynamics of close relationship are part of the day to day.

In La Guajira, there are still so many problems associated with education that receiving Venezuelans is not a priority. In fact, the local population perceives migrants as a ‘threat’, believing that they compete with them for access to resources and benefits, which are extremely scarce and restricted in the region. “In this part of the country, the Colombian population that receives children and adolescents is in similar conditions, so they wonder why Venezuelan migrants receive aid that nationals do not,” they say.

At the last level –that of schools– it was found that although in the capital of the country educational institutions receive Venezuelan children, they do not generate particular actions to integrate them into the student community because they consider that doing so would be a form of discrimination. “We treat them as equals,” they argue, while Urbano explains, “xenophobia is not recognized in the face of these children: “In Bogota schools, the answer was that their classrooms do not have cases of discrimination when in fact they do, although they consider them insignificant.” The researcher emphasizes that the low or nonexistent perception of xenophobia that is observed in Bogotá is also reflected in the other areas studied, leading to the conclusion that no actions are being taken in any of the three levels to detect and counteract it.

One example is that in La Guajira, to refer to Venezuelan girls, many use expressions such as “white plates,” referring to the plates used by Venezuelan vehicles. Likewise, the community is full of the imaginary that Colombia is doing them ‘a favor’ by allowing them to enter our territory, which should imply ‘gratitude and silence’.

“This shows that there are problems of ‘microxenophobia’ that are not evident to school actors,” Díaz says.

In border areas, Venezuelan children and adolescents often enter, and the familiarity of cultural exchange facilitates the processes of inclusion and adaptation. During flag raising, for example, and as has been the case for decades, it is possible to listen to the anthems of both nationalities and there are some initiatives – still timid and insufficient – to apply curricular adjustments that facilitate the integration of migrants, based on issues related to the culture or sciences of the neighboring country. In contrast, in the country’s capital, only one of the five schools evaluated carried out this type of action to integrate Venezuelan migrant children who made up an important group of students.

“In Cúcuta we also identified strong educational leadership from the principals, who are excellent managers,” the researchers highlight. This is the case of a principal who during the pandemic organized his entire community, including parents, to get educational guides to enrolled children who were in Venezuela and who, due to lockdowns and border closures, could not attend class or connect to the internet. Likewise, there were cases of school directives that sought support from international organizations to build a dining room in which they could give snacks to migrant children.

Professor Urbano concludes that “in general, there is a great loneliness of schools, especially teachers, to generate responses that integrate this population into the education system. Ultimately, it is the teachers who are challenged to integrate the migrant population adequately into the education system. For me they are the heroes and heroines of this situation.”

Beyond these particular initiatives, there are no clear guidelines aimed at integrating the entire educational community in terms of curricular transformations. “It is important to build a more intercultural environment, understood not as the leveling of standards, but as an enrichment of the curriculum and pedagogical practices, which recognize the identities of Venezuelans in the same way as we should recognize the identities of indigenous people, Afro-descendants and other groups that make up the territory. We want to bring this to policymakers to contribute to the right to quality education for migrants,” Díaz concludes.

Source: Characterization of Venezuelan Migrant Childhood and Adolescence in Colombia: The Study. Colombian Institute of Family Welfare (ICBF), 2022.