Indebtedness, a condition aimed by those who want their own house in Colombia

By: Alejandro Ramírez Peña

Photos:

Economics and Politics

By: Alejandro Ramírez Peña

Photos:

In Colombia, loans are the most common and natural way to achieve anything you may desire or need, no matter if such a desire is for goods, academic programs, or trips. Among that collection, a house is undoubtedly the most wanted.

According to the Banco de la República, in its report Financial Stability in the Second Semester of 2019, out of the total debt level of families, two thirds ($156.1 billion) corresponded to consumption credits and the rest to housing credits (approximately $87.7 billion).

In spite of the right to have a decent house, as embodied in Article 51 of the Political Political Constitution of Colombia, the public policies in the country have focused on boosting the purchase through financing, which implies getting into a long-term credit commitment, which is, additionally, not easy to get and, on some occasions, difficult to honor.

According to the most recent National Survey on Life Quality (2019), 41.6 percent of the country’s families lived in fully paid own houses; 4.6 percent were paying for it; 35.7 percent lived renting or subletting; and 14.1 percent did it with the owner’s permission, without paying anything.

This picture of the country motivated Professors David Hernández Zambrano, from the Center of Ethics and Citizenship Learning (Phronimos), and Yira López Castro, from the Faculty of Law, both from the Universidad del Rosario, to explore the topic from the standpoint of the Constitutional Court and public policy in the research work "Indebtedness for access to housing: The justice models behind the constitutional protection to debtors" (published in 2020).

The Constitutional Court has highlighted that a mortgage debtor is a vulnerable end or the weakest member in the credit relationship with the financial system. In sentence C-1140 of 2000, it pointed out, “The creditor imposes the contract conditions, whereas the debtor—the weakest party in the relationship—is limited to the role of accepting the rules previously set forth by the former. The party requesting a loan for purchasing a house is undeniably subjected to the contract provisions of financial institutions (...) (C-1140 de 2000 M.P. Hernández Galindo)”.

In fact, the researchers found that all conditions are set to favor the financial system, not the debtors, who are not protected in the debtor–financial institution relationship, which is almost always a long-term agreement; the 2021´s law 2079 on housing states that a housing credit status must have at least a 5-year term for repayment.

Such a provision implies that, in the event of unforeseeable circumstances such as risks connected with unemployment, disease, or the death of one of the members of the household, affecting the chances of paying for the mortgage credit, the debtors may lose the ownership of the property.

That is an alarming fact in times of a pandemic, especially if we consider that the house has become a protecting place, a shelter that also demands new requirements. “The house has taken on a special dimension and has been combined with some decent conditions for work. It demands other areas that were not considered as important before, such as a room for study and services that enable working and studying in the same room,” Hernández observes.

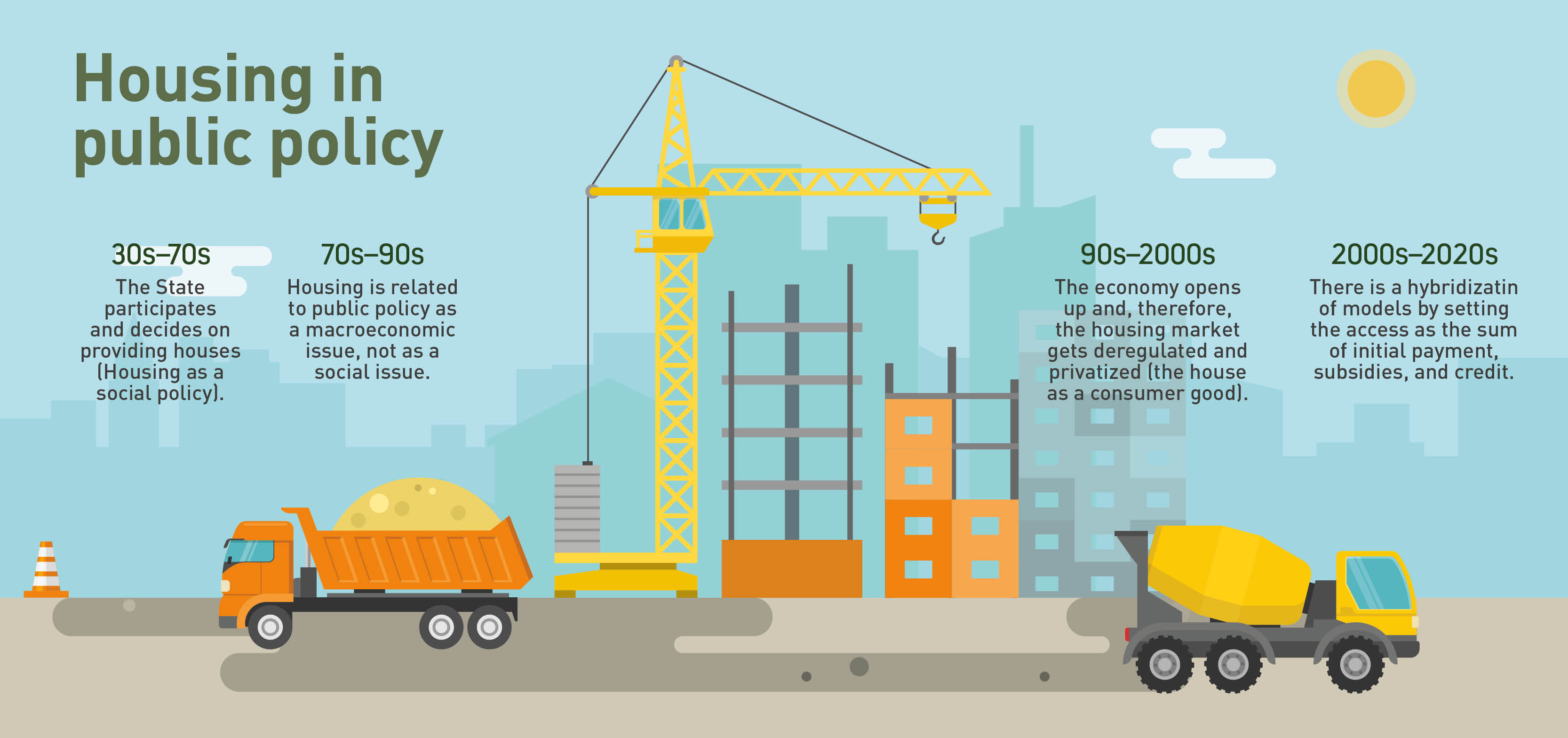

In this sense, the researchers revealed some evidence of the debtor’s unbalanced relationship with the financial system. They analyzed the public policy established for the sector between 1920 and 2020 to identify where this system originated, when things started to come up this way, and since when our society adopted the concept of debt as a way to get a house.

They wanted to understand why the compound “work, savings and debt” is the normal way to have access to their rights. In other words, they wanted to learn why debtors need the financial system to “like” them and grant them a loan to purchase a house, despite the fact that it will take them almost their whole lives to repay such obligation.

“What we pinpointed was that there was a decision, especially by the public policy of the 1970s onwards, made for housing to support many sectors, such as construction, so it may in turn generate employment,” López explains. “It was also a policy that was intended to compel people to work in rural areas, who could be—according to that development plan—inefficient in such tasks, come to the city, work in the construction industry, receive a payment for their work, and set aside part of those earnings to get indebted.”

Therefore, the process of self-construction, in which all the family members were involved in gradually saving money and building their homes, changed in the 70s. At that moment, the boom of the construction companies linked to the financial system started, to the extent that today urban developments have the names of corporations such as Las Villas.

Another aspect that stands out about those decisions taken a little over 50 years ago is the fact that since then, houses have become market or private goods. A particular issue, as in different systems in other countries, is public houses, which enable some actions, such as the regulation of renting prices or developing residential buildings for low-income people in downtown areas, which in turn improves access to a house and reduces commuting time for people.

Furthermore, in Colombia, social-interest houses (VIS, Spanish acronym) are considered private because people are also indebted to purchase one to boost the financial system.

For Yira López, a professor at the Faculty of Law of Universidad del Rosario, “The goal would be to have a policy for controlling constructing companies so we can have serious developers that abide by transparent solvency standards. Thus, some events, such as the Space Residential, could be avoided, as well as many other events happening in different Colombian cities”.

The study allowed the researchers to sketch some characteristics of the Colombian debtor. For example, they are not homogeneous and do not belong to different social economic layers. Some debtors aim at having a social-interest house with subsidies; the one that receives other types of aid or lower interest rates for purchasing a new house (not VIS); and the debtor who does not even need a loan gets one to buy a more costly property.

However, despite the multiple indebtedness schemes offered in the market, many people still do not have a clear path to get a house because they cannot profit from the financial system and have no saving possibilities, not even for the minimum required to apply for a subsidy.

For this dilemma, López warns, “In 2014, the country created a free housing program, which was criticized given the uncertainty of the sustainability of the budget for this program and because it does not focus on the qualitative deficit, as the houses are built in locations away from productive areas and do not correspond to the conditions expected for an adequate house.”

In the conceptual view of the researchers, that situation has occurred because housing policies have focused on showcasing successful figures of the number of units built and sold, instead of ensuring the protection of citizens’ rights to housing.

Additionally, the State has not controlled the prices either, as indicated by the high cost of social-interest houses (average price is $123.7 million, compared to a minimum salary of $908,526) and materials used for construction. The responsibility for the prices was left in the hands of the market, and in most cases, such prices tend to rise, the authors of the study emphasize.

It is worth mentioning that, regarding subsidies, the program Mi casa ya (My house right away) is planned for households earning less than eight effective legal monthly minimum salaries ($7,268,208 today). Through this program, the families receive a monetary subsidy of 20 to 30 effective legal monthly minimum salaries (SMLMV, Spanish acronym) for the initial payment and a 4 to 5 point interest rate coverage, depending on the incomes and type of the property.

The point is that, although there are offers to purchase, the main issue is still the debt level + subsidies model (financing the demand), which implies that the house is more of an economic concern than a constitutional right.

Given this scenario, the researchers point out some solutions for debtors, some solutions that already exist and some that should be created. In the first case, they underline that the Financing Superintendency has the power to protect the financial consumer, a category that embraces the indebted proprietors who are in turn able to file complaints and reports related to financial institutions.

“Anyway, when someone is a debtor and proprietor, they have a relationship with a construction company. This situation turns them into real-estate consumers, which enables them to initiate complaints and demands against construction companies at the Superintendency of Industry and Commerce (SIC) in case of any hindrance,” Hernández stresses.

“This possibility involves a type of protection. However, such protection gets obstructed if the construction company files for insolvency because the prospective decision in favor of the consumer may not become effective. In these situations, there is no particular protection.”

Regarding the solutions that must be created, López considers that one solution is to strengthen monitoring, surveillance, and control over construction companies and to ideate measures to create environmentally sustainable houses, with cheaper materials.

The objective would be to have a control policy over construction companies so we have serious constructors who abide by transparent solvency standards. In this way, we can avoid some events, such as the Residential complex and many others, that occurred in different Colombian cities. We should convey to construction companies that their activities pose risks and, consequently, monitoring, surveying, and controlling are required, but this should not be a task spread across multiple institutions,” the professor states.

In view of the unbalanced relationship between debtors and the financial system, the researchers assert that we should urgently establish a relationship that enables renegotiating with banks in such a way that the house is considered—apart from being a good in the market—as a right and that politics should treat it in that sense.

Finally, they recommend that public policies should include those who use the good as proprietors, not just as tenants and lessees. Therefore, protection measures must be defined in general, not in particular, in terms of indebtedness.

In view of the unbalanced relationship between debtors and the financial system, the researchers assert that we should urgently establish a relationship that enables renegotiating with banks in such a way that the house is considered —apart from being good in the market—as a right and that politics should treat it in that sense.

The Constitutional Court’s rulings show the judicial attempt to solve the current situation of housing and debt. The Court has adopted three approaches to justice in the relationship between the debtor and creditor.

Housing debtors as the victims of the State’s decisions (the Upac case). Model of corrective justice. Based on economic damage to debtors, the interests considered are patrimonial. The values that underpin the decision are judicial security and debtors’ autonomy. The step or action to take, acknowledging the responsibility of the State, is the direct compensation by the Constant Purchase Power Unit (Upac) for the people impacted.

As the holders of the right to housing. Model of distributive justice. The interest the Court considers is the right to a decent home. The judging method is centered upon the values of equity and solidarity, and the step or action to take is public intervention in contracts for access to housing (Law 546).

As the holders of the right to a contract just process. Model of procedure in justice. The debtor is considered a weak party in the contract. The main interests are a just process and the values that support the decision are formal equality (the parties are free to enter into a contract) and promise fulfillment. Therefore, the adequate step or action is to guarantee the compliance of contracts.

David Hernández Zambrano, a professor and researcher at the Center of Ethics and Citizenship Learning (Phronimos) at Universidad del Rosario, explains: “the house has taken on a special dimension and gets combined with decent conditions for work. It demands other areas that were not considered as important, such as a room for study and services that enable working and studying in the same room.”